In 1995 a man named McArthur Wheeler was convinced that lemon juice was not only a good drink mix, but also an invisible ink maker. He was so convinced of that fact that he rubbed it all over his face and went on to rob two banks in Pittsburgh. When the cops reviewed the security tapes and saw Wheeler’s face, they quickly identified and apprehend him.

While Wheeler didn’t come away with any riches that day, he did inadvertently help two psychologists articulate a concept that describes our inability to determine our own incompetence. As David Dunning and Justin Kruger wrote:

“When people are incompetent in the strategies they adopt to achieve success and satisfaction, they suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it. Instead, like Mr. Wheeler, they are left with the mistaken impression that they are doing just fine”

Picture the coding engineer who couldn’t write a line of code free of bugs. Or the keynote speaker at your last staff meeting who bored everyone to sleep. Or in the world of pop culture, think of that particular contestant of The Voice who couldn’t carry a tune in the shower, yet didn’t understand how they weren’t chosen to compete on a team.

Each of these people thought they were highly capable at what they set out to do, but no one recognized their shortcomings. It’s a position we’ve all found ourselves in at some point or another—where our eyes get bigger than our stomach and, after we dive in, we quickly (and hopefully) find out that we’ve bitten off more than we can chew.

The phenomenon is something that’s come to be known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect, and it’s something we should be on the look-out for as we set goals that will push us into the “unknown”.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

This principle first got its wings twenty years ago in a 1999 paper entitled “Unskilled and Unaware of it”. Inside, researchers David Dunning and Justin Kruger tested a broad array of scenarios to see how competent people felt they were versus how competent they actually turned out to be.

Participants were asked to be the judge of how funny jokes were, to use grammar correctly, or to tackle logical reasoning questions from the LSAT exam. Then, they were asked to assess their own performance on these tasks as well as the performance of their peers. And time and again, across a variety of experiments, under-performers thought they did well.

What you might not expect to find out is that high performers thought they were on-par or worse off than their peers. They didn’t realize they had done well until they were shown how well they fared.

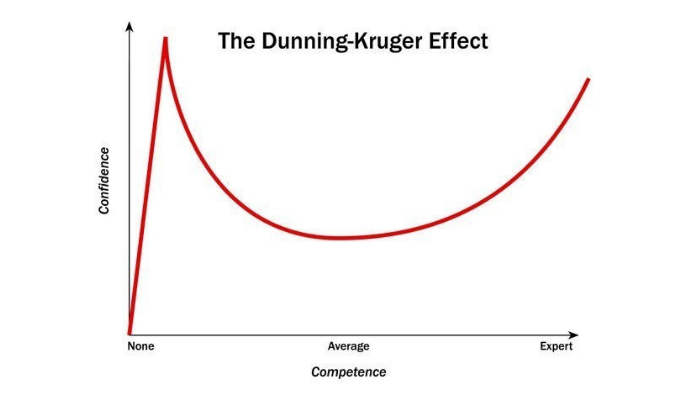

This relationship between being overconfident in our meager abilities and lacking confidence in our strengths, tends to form a reverse bell-curve:

In the beginning, we’re confident in our ability because we don’t know what we don’t know, which means we’re apt to take action. As we become more competent in our skills, we learn what we don’t know. We have the competence to know we may be okay at something, but the confidence to admit that others can likely do it better than we can. And we keep trying to be better. However, as we reach the “expert” range of the model, we are aware of our abilities as well as our faults. Given we understand the areas where we fall short, our confidence in our performance drops. We are better than we realize. From there, the challenge is to continue to seek out improvement.

Being able to fully traverse the curve and gain confidence where it matters most, comes down to our ability to receive and process feedback and training.

Using Feedback to Make Progress

Those at the front-end of the curve neither have the skills to do the task at hand well, nor have the abilities to assess their own performance accurately. They look around and think they are better than their peers. They don’t seek out ways to make improvements because in their eyes, they are doing a great job. (This happens even in scuba diving, where the Dunning-Kruger Effect accounts for a number of scuba accidents due to diver error.)

These people need to seek out feedback. Properly taking in feedback and using it to better your performance is where growth occurs. Although it might mentally feel like taking a step back, adopting a growth-mindset will improve your performance and fuel your eventual success.

On the other end of the spectrum, people who attain “expert” levels of competence make assumptions about their own performance. These people need to actively seek out feedback as well. When they solve a problem, they tend to believe that their peers can, too. As one study concluded, “Because top performers find the tests they confront to be easy, they mistakenly assume that their peers find the tests to be equally easy. As such, their own performances seem unexceptional.”

Even if you’re competent, don’t assume you can’t stand to benefit from seeking out ideas for improvement. When we don’t seek out feedback, it’s impossible to attain a certain level of mastery.

Looking for Feedback

When it comes down to it, feedback isn’t always as forthcoming as we may expect it to be. Especially if it’s negative. Think about it. Do you want to tell the person next to you that they’re terrible at something, especially if they think they’re great at it?

No. (Or at least we hope not.)

As Kruger and Dunning explain, “People seldom receive negative feedback about their skills and abilities from others in everyday life.”

However, by seeking out honest views from others, you are opening yourself up to the understanding that you may be able to improve upon what you’re currently doing. And face it, no matter how good we think we are, there is always room for improvement.

When you are seeking out feedback (or giving it, for that matter), we recommend having a conversation first about how you like to receive it. After all, everyone communicates differently. Some people may like brutal honesty and others may like feedback delivered a little more gently. Being candid about someone’s performance requires giving this information in a way that it can be best received. An understanding about how to share this feedback will allow you to process it without getting bogged down by the delivery style.

Seeking out Training

Obtaining valued advice on how we can improve is the first step in the process. Next, we have to put that feedback to work through training.

When people are provided training on a subject, they become better versed in what they didn’t know before. This newfound knowledge lets them be more realistic about their previous skills.

When given training after an assessment, researchers found that those people who previously greatly overstated their abilities revised their self-judgements dramatically. Therefore, not only do the poorest performers learn the skills to improve their own performances, but they also become more self-aware at how much they know as well as how much they know in comparison to their peers.

It’s a win-win.

Keep An Eye on the Prize

If you think you’re knocking it out of the park in everything you do, your best bet is to find some trusted peers that can provide you with frank feedback to confirm or disprove your theory.

Maybe you truly are the best of the best, or maybe you simply don’t know what you could do to improve. Either way, by opening yourself to advice as well as the possibility to improve, you can continue to learn the skills that will move you in a positive direction along the Dunning-Kruger Effect curve and bring you to the next level of performance.